|

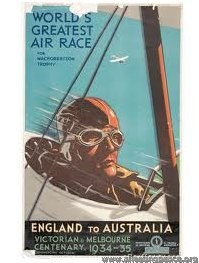

The Greatest Air Race (again): The 1934 MacRobertson Race from Mildenhall to Melbourne

The MacRobertson Race itself - probably the most successful air race of its kind, ever - is spendidly and copiously documented elsewhere. What is more difficult to find, is information about the people involved; many of them have fascinating stories, it turns out. I've also discovered that they got the handicap results wrong (although it's probably a bit late to say this, now, I suppose); and in these pages you can find, in exhausting detail, my reasoning. Whichever way you look at it, David and Kenneth Stodart in the Courier woz definitely robbed. |

Home

Link Page - MacRobertson Race

- Details

- Hits: 6229